Share

The 6 Stages of Play in Child Development (And How to Support Each One)

Learn how to engage with your child during each stage of play and the difference between unoccupied, solitary, parallel, and cooperative play.

What Are the Stages of Play in Early Childhood Development?

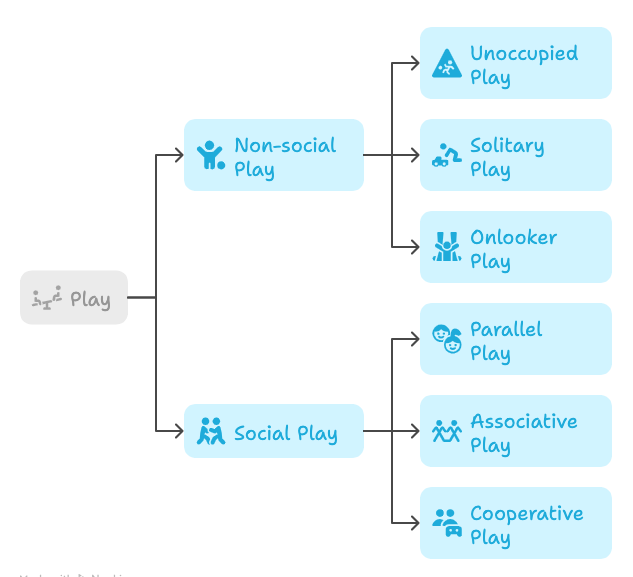

Nearly one hundred years ago, sociologist Mildred Parten developed the theory of the 6 stages of play in early childhood social development. She observed a group of preschool children aged 2 to 5 and noted the different ways in which they played socially and non-socially. In her doctoral dissertation, she first defined the six stages of play that are still recognized today:

The 6 Stages of Play

Parten found there were two general types of play, non-social and social, which she then broke down into the six stages of her theory.

- Unoccupied Play

- Solitary Play

- Onlooker Play

- Parallel Play

- Associative Play

- Cooperative Play

Both social and non-social stages of play have their place in early childhood development, and children generally progress through them as they grow. However, it’s not a strict hierarchy—many children move back and forth between these stages as they develop. And while Parten noted general ages at which children participated in certain types of play, these ages are guidelines rather than strict rules.

Mildred Parten’s 6 Stages of Play

Why the 6 Stages of Play Are Important

Child psychologists and early childhood development specialists may use these stages of play to evaluate and assess children for age-appropriate behaviors. An understanding of the 6 stages can help parents encourage age-appropriate play styles and recognize when a child might need further guidance or professional help. Knowing the stages also helps parents avoid pushing their kids into types of play they might not be ready for.

For example, expecting a 2-year old to regularly play cooperatively with others is unrealistic. But if a 5-year old still only mainly engages in solitary play, this could indicate a need for further observation or support in developing social skills. To learn more about your child’s play stages, watch them in group settings with other children and look for the behaviors associated with each stage.

The 6 Stages of Play: Explanations, Examples, and Tips for Parents & Teachers

Mildred Parten’s 6 stages of play explain how children use play to learn about the world around them, expanding outward from understanding their own body and its movements to learning to function in social groups.

Note: The ages given here are guidelines only. It’s normal for children to move back and forth between stages and progress at their own speed. If you have any concerns about your child, consult an expert.

What Is Unoccupied Play?

Unoccupied play refers to a type of free, self-directed play where infants engage with their surroundings and their own bodies without any set objective or adult guidance.

Most Common at Age: Birth to 3 months

Characteristics of Unoccupied Play:

- Seemingly random movements, often repetitive

- Watching others closely, but not interacting

- Reaching for an object without necessarily grabbing it

Examples of Unoccupied Play:

- Kicking legs and waving hands

- Watching a crib mobile or ceiling fan spin

- Splashing water in the bath

- Grabbing their own toes

- Pointing at people or things

What Unoccupied Play Looks Like:

Babies begin to play from the moment they’re born. Their earliest play involves their body itself, as they try out different movements to see what the results will be. Though these behaviors may seem meaningless to adults, they’re actually a very important part of early motor skills development. Infants are learning how to process sensory input from the world around them, gathering information from what they see, hear, and feel.

How Parents/Teachers Can Support Unoccupied Play:

- This is the age at which experts strongly recommend “tummy time,” which helps strengthen shoulder and neck muscles. Simply place your child on their stomach for a few minutes each day. As they get older, you can place toys nearby for them to focus on and reach for.

- Provide safe, stimulating places for infants to explore. Give them room to wiggle and move, and provide new objects to look at, sounds to hear, and other sensory experiences like sensory mats or mirrors.

- It’s okay not to interact with your infant constantly! In fact, they need time for unoccupied play on their own, allowing them to process their bodies and environment at their own pace.

What Is Solitary Play?

Solitary play—also called independent play—is a developmental stage where a child plays on their own, without engaging or interacting with others.

Most Common at Age: 3 to 24 months

Characteristics of Solitary Play:

- Independent

- Highly focused

- Experimental

- Often repetitive

- Unaware of or unresponsive to other children playing nearby

Early Examples of Solitary Play:

- Stacking blocks

- Throwing items away over and over again

- Shaking a rattle or squeezing a squeaky toy

- Banging objects together or on a hard surface

Older Examples of Solitary Play:

- Coloring or drawing by themselves

- Looking through a book

- Singing to themselves as they play with stuffed animals or dolls

What Solitary Play Looks Like:

This is the stage at which play becomes more recognizable to parents. Children start to interact with toys and other objects, often in a repetitive way. They become extremely focused and tend to ignore others around them, including other babies and even parents and caregivers. This is completely normal! Kids are now starting to develop concentration, imagination, and problem-solving skills. Solitary play at this age is vital to development, as children take their first independent forays into the world.

Note: Solitary play continues throughout childhood. Many kids are content when they’re playing on their own at any age. But as children get older, they should combine independent play with more social forms of play. Even if they prefer to play by themselves, it’s important for them to develop the social skills needed to play and interact with others. However, some solitary play is perfectly fine at any age.

How Parents/Teachers Can Support Solitary Play:

- Be tolerant of noise and mess. Toddlers haven’t mastered gross and fine motor skills yet, and they can’t always control their movements or voices. When you can, let them play and express themselves freely. (This doesn’t mean children don’t need guidance and boundaries, even at this age. It just means knowing when it’s worth reining in a child’s behavior and when to just let them do their own thing.)

- Allow kids time to play on their own and in any way that they like as long as it’s safe. Don’t feel the need to step in and show them how something works—let them experiment and figure it out on their own. Observe their play, rather than trying to direct it.

What Is Onlooker Play?

Onlooker play, sometimes called spectator play, is a stage of development where a child watches others play but doesn’t join in themselves.

Most Common at Age: 2 to 3 years

Characteristics of Onlooker Play:

- Closely watching other children or groups of children playing

- Laughing, cheering, or otherwise responding to the action

- Asking questions or making comments to players or others nearby

Examples of Onlooker Play:

- A toddler watches other kids playing tag, closely focused on the action

- Child asks a group of children playing with playdough, “What are you making?”

- A preschooler listens as a group nearby pretends to run a restaurant and laughs when one child pretends to serve “mud soup”

What Onlooker Play Looks Like:

Onlooker play is a transition stage between non-social and social play. Kids spend time watching others in their general age group, observing their actions but making no effort to join in. They might ask questions, laugh with or cheer for the players, or make comments to others about what’s happening. For now, though, they’re content to sit on the sidelines.

Parents may sometimes worry that onlooker play means their toddler is too shy to get involved, but that’s usually not the case. Generally, kids are just subconsciously waiting until they feel confident that they understand the “rules.” They learn so much through these observations, developing an awareness and understanding of how social groups function.

As with solitary play, kids return to this stage from time to time as they get older. This can happen when they’re meeting new groups of people, learning how a game or toy works, or just want to know more before deciding to join in. By the time your child reaches school age, they should spend less time in onlooker play and more in social forms of play instead.

How Parents/Teachers Can Support Onlooker Play:

- Recognize that watching others is an important way to learn. Kids pick up many social-emotional skills simply by observing those behaviors in the people around them. Model good social behavior, and point it out when you see it too. “Look at those kids sharing toys in the sandbox! That looks like fun.”

- Don’t push your child to join in. Most kids will make their own moves toward social play when they’re ready. Sit with them and watch, answering any questions or responding to comments. If they ask if they can join in, gently encourage them to ask, “Can I play with you?”

- Know that even older kids engage in onlooker play from time to time, especially in new situations. For example, a fifth grader who’s new at school might watch others playing soccer on the playground for a day or two before asking to join in. Give kids space to build comfort and confidence, and try not to step in unless it’s truly needed.

What Is Parallel Play?

Parallel play is a developmental stage where toddlers play next to one another, often doing similar activities or using the same toys, but without interacting or influencing each other’s play.

Most Common at Age: 2 to 3 years

Characteristics of Parallel Play:

- Independent but not solitary

- Little or no interaction between children

- Minimal sharing or cooperation

- Comfortable with other kids playing nearby

- Some observation and imitation of others

Examples of Parallel Play:

- Four kids finger painting at the same table, but each is only focused on the pictures they’re making. They don’t talk to each other about their work.

- Two children playing in the sandbox, digging their own holes and making their own structures. One quietly watches the other fill a pail with sand and dump it over to make a tower, then does the same themselves, but doesn’t say anything to the other child.

- Three kids play in the same room. One sings quietly to themself as they put together a puzzle, one builds structures out of LEGO® bricks, and the third draws pictures with crayons. A fourth child comes in, sits down nearby, and begins to look through a picture book, comfortable with the presence of the other kids.

What Parallel Looks Like:

Parallel play is another transition stage, but this stage has a more actively social aspect. In parallel play, kids play side-by-side with the same toys or activities, but don’t directly interact with one another.

Sometimes they watch each other or imitate what they see, but they’re still more focused on their own play. Parallel play is an important bridge between solitary and social play.

Walk into an early preschool classroom, and you’re likely to see a lot of parallel play. Three kids might be playing with blocks, but they’re all building their own structures. They’re more likely to talk to themselves than with others, or just play quietly. It may seem like solitary play, but these children are actually developing important social skills. They’re becoming comfortable around others and learning new ideas by watching and imitating.

The more a child engages in side-by-side play, the more they learn to tolerate the presence of others. Parallel play actually helps them fine-tune their concentration, since they may need to tune out other actions and noises while they play. It also develops their spatial awareness, giving them the ability to move around in crowded spaces without running into each other.

Older kids may participate in parallel play too. A new kid on the playground might watch others kicking a ball around, then start kicking around another ball on their own nearby. It’s a subtle way to express interest in more social play before taking more deliberate steps to join.

How Parents/Teachers Can Support Parallel Play:

- At younger ages, playgroups are often all about parallel play. It may seem like there’s no point in getting kids together just so they can play on their own, but it’s actually a valuable experience. Children must become comfortable with having others nearby, especially those their own age. Start playgroups early to encourage your child to tolerate social situations, even if they don’t interact.

- In groups, provide multiple versions of the same toys so kids can play side-by-side. For instance, have several sets of crayons and coloring books, more than one puzzle, or separate bins of building blocks kids can use.

- Provide plenty of space for kids to play near each other without crowding each other out. When kids play more active games, help them learn how to move around a space while being aware of others. “Your jumping game looks like fun! Why don’t you move over here a bit so you don’t run into Olivia and her block towers?”

What Is Associative Play?

Associative play is a stage of social development where children play near each other, interact, and share materials, but their play isn’t coordinated around a shared goal or structured activity.

Most Common at Age: 3 to 4 years

Characteristics of Associative Play:

- Shared materials or toys, but separate goals

- Increased interaction and conversation

- Play is usually unstructured

- Often includes preferred playmates

- Kids begin to share and resolve conflicts as they play

Examples of Associative Play:

- Two kids share a set of building blocks, chatting while they work, but each still building their own structures. From time to time, they comment on what the other has built.

- Four children coloring pictures talk to each other about what they’ve created, sharing the contents of a crayon box and asking each other for the colors they want. When two kids both want to use the red crayon at the same time, they eventually figure out that they need to take turns.

- One child shows another how to throw sticky balls at a target, offering tips for getting closer to the center. They take turns, but don’t keep score or compete in any way, just enjoying each other’s company and the challenge of the game.

What Associative Play Looks Like:

This is the first stage where kids truly begin to regularly interact while they play. Kids talk, share toys, and demonstrate and imitate activities and games. However, at this stage, children don’t fully organize or collaborate during play—in other words, they don’t have a clearly defined shared goal. It’s essentially parallel play, but with interaction between kids.

Older preschool classrooms host a lot of associative play. This is a huge social leap for early childhood development—showing an interest in what others are doing and joining in the activity in their own way. To reach this stage, kids need language and communication skills, social awareness, cooperative skills, some degree of empathy and self-control, and tolerance for those different from themselves.

Older children return to associative play from time to time, especially in creative endeavors. For instance, fourth grade students might share a box of art supplies, but each make individual creations. They talk and laugh while they work, sharing ideas but ultimately focused on their own work.

How Parents/Teachers Can Support Associative Play:

- Allow time for free play without restrictive rules or structure. Provide open-ended toys that encourage use by multiple children at once, such as building blocks or art supplies.

- Encourage conversation as kids play. “Emmet, your tower is so tall! Can you tell Liam how you did that?” or “You’re doing a great job of sharing the kitchen toys! What are you both making?”

- Model social skills and awareness. “Taylor, you’re taking up a lot of space on the table, and Ashton doesn’t have much room. Could you move over a bit and try to keep your painting supplies on your side of the table, please?’”

- Teach conflict resolution skills. As kids learn to share and play together, conflict is inevitable, and adults must demonstrate and model the right behaviors. “Jaxon, you grabbed the green crayon even though you knew Emma was using it. Remember to ask first: ‘Emma, are you done with the green crayon? Can I use it now, please?’” or “Charlotte, you and Noah can’t both use the swing at the same time. What can you do while you wait for him to finish his turn? Noah, remember that Charlotte is waiting for the swing, so you get two more minutes, then it’s her turn.”

- Occasionally nudge kids into true cooperative play, but don’t insist on it. “I love the buildings you’re each making! What if you worked together to build a whole town?” or “Morgan, it looks like Lin wants to kick the soccer ball around too. Could you two try playing with it together?”

What Is Cooperative Play?

Cooperative play happens when children work together toward a common goal, using communication, teamwork, and problem-solving to complete a shared task or activity.

Most Common at Age: 4 to 5 years and up

Characteristics of Cooperative Play:

- Shared materials and goals

- Players have different assigned goals in the game

- Players agree on the rules up front or develop them throughout

- Regular communication amongst players

- More autonomous conflict resolution and compromise

- Longer play sessions that often involve creativity and imagination

Examples of Cooperative Play:

- Four children play “House” together. One is the mom, one is the grandma, and two are the kids. They invent and role play domestic scenarios together.

- Two children create a new ball game together involving bouncing a ball off the wall and ground, with complex rules and scoring. When other kids come along, they invite them to join in, explaining the rules of the game.

- Three children work together to put together a jigsaw puzzle. They agree on a plan (“First we’ll do the edges, then work on the middle”) and assign roles (“Katelyn, you work on the pink pieces of the house, and I’ll try to put together the sky.”) They chat while they work, sometimes about the puzzle and sometimes about other topics.

What Cooperative Play Looks Like:

This is the final and most social of the 6 stages of play. Children collaborate as they play, sharing the same materials or toys, following the same set of rules, and working together for a common purpose. They communicate often, verbally and nonverbally, usually to specifically advance the game.

For older children (post-preschool), this is the most common form of social play. Their games and play activities last longer, are more complex, and may involve larger numbers of participants. Kids develop more social awareness, understanding what’s expected of them and what to expect of others. They tend to resolve conflicts on their own when they can, and while they may invite adults to play, those adults must follow the “rules” developed by the children. For example, in a game of The Floor is Lava, a child might say, “No, you can’t walk there! That part of the floor is hot lava!”

The benefits of cooperative play are numerous and well-established. Children develop social skills through all the stages of play, but this is the stage where they truly need strong social skills to succeed and thrive as part of the group. They’re learning by experience and nearly all will hit rough patches from time to time. Learn much more about the benefits, challenges, and importance of cooperative play here.

How Parents/Teachers Can Support Cooperative Play:

- Provide big open play spaces and materials to spark imagination (dress-up clothes, building toys, toy food and kitchen utensils, loose parts boxes, etc.). You can also offer prompts to get them started: “Let’s pretend this jungle gym is a tree in the actual jungle!” or “What if you built a model of our town?”

- Allow kids to develop their own games and play activities. Give them room to create their own rules, asking questions to guide only if needed: “How will you decide the winner?” or “What do you think you should do first?”

- Encourage social awareness and model good behavior. “Amelia, I don’t think Sarah has a job in your store yet. Why don’t you ask her what she’d like to do?” or “Your game of Aliens and Puppies Freeze Tag looks so fun! But you keep running into the area where Quinn, Parker, and Riley are playing airport. Can you move a little further down the playground and give them some room?”

- Give kids time to resolve conflicts independently before stepping in. Then, guide them toward the right behavior. “Looks like Lane and Allie both want to be the leader. Can you take turns, or share the leader role?” or “You all agreed on the rules up front, but this particular rule seems to be causing a lot of arguments. Do you think you should consider changing it?”

- Recognize good collaboration and teamwork when you see it. “Way to go! You managed to get every member of your team through the obstacle course by helping each other! I’m so impressed!” or “Alex, I really liked the way you found a way for Miguel to join in your game halfway through. He really wanted to play, and you all had so much fun together.”

Other Types of Play

While Parten’s 6 stages describe the social aspects of play, there are many other terms that child development experts use to describe the way kids play. Experts have determined that there are 12 to 16 ways that children play. Here are a few you may hear as a parent or teacher.

Other Ways Children Play

- Attunement play

- Physical play

- Social play

- Constructive play

- Imaginative or pretend play

- Functional play

- Symbolic play

- Expressive or creative play

Attunement Play

Attunement play is one of the earliest forms of interaction between an infant and caregiver, laying the foundation for emotional connection. This type of play fosters trust, empathy, and emotional regulation, supporting healthy social and emotional development. It includes

- shared eye contact

- smiles

- facial expressions

- responding to one another’s coos, babbles, and gestures

These “serve and return” exchanges—where the baby initiates with a sound or movement and the adult responds with attention, smiles, or soothing touch—help build secure attachment.

Example: A father and baby make silly faces at each other, laughing as they do; a baby points to a toy and a caregiver brings it over, making it dance for the baby.

Physical Play

Physical play uses the body in active ways. Babies engage in this type of play from a young age, though it advances when kids can walk on their own. It helps to

- build strength and improve overall physical health

- develop gross and fine motor skills

Example: Running, jumping rope, riding a tricycle or bicycle, dancing, skipping, playing a sport

Social Play

Social play is any form of play where kids interact and talk with each other as they play together or near each other. This can involve:

- interaction related to the activity or game they’re enjoying

- conversing while playing side-by-side

Example: Team sports, parallel play, associative play, cooperative play, board games, imaginative games

Constructive Play

In constructive play, participants build or create something with a specific purpose. They may

- play collaboratively in a group

- play with one other child to build something

- play individually to make something on their own

Example: Working together to put together a puzzle, creating a large mural, building a city from blocks, writing and acting out a skit or play

Imaginative Play

Imaginative play, or pretend play, occurs when kids use their imagination heavily in an activity or game. They may

- make up stories to share with each other

- act out themselves or with toys

- invent entire new worlds with characters and storylines

Example: Playing house, school, or hospital; dressing up in play clothes; having a stuffed animal tea party; pretending to be a superhero

Functional Play

In functional play, children are learning how something works, with the essential question of, “What happens if I do this?” Here are few characteristics of this type of play:

- It often includes repetitive actions

- It’s especially common with very young children

- Kids of any age engage in functional play when they encounter something new

Example: Throwing a ball in different ways to see how high it bounces, pushing all the buttons on a toy in turn or at once, stacking objects until they fall over

Symbolic Play

This form of imaginative play turns objects or actions into whatever kids want or need them to be. For example, a red block becomes an apple for their game of grocery store or a large box becomes a space ship.

- Children use symbolic play more when they have fewer structured toys at hand

- Symbolic play helps develop stronger creativity and problem-solving skills

- Requires imaginative and abstract thinking

Example: A stick becomes a magic wand, a box is a castle on Mars, a blanket is a magic cape, a wooden spoon is a telephone

Expressive or Creative Play

In this type of play, children share their thoughts, feelings, and creativity through their activities. It includes

- Creative and joyful activities like singing, dancing, drawing, or writing

- It can also be a way to express negative thoughts or feelings: “I’m coloring black rain clouds because I’m angry.”

Example: Singing out loud to themselves or an audience, drawing pictures to share with others, writing poems when they’re sad, or putting on a puppet show

How to Support Healthy Play at Every Stage

No matter what stages of play your child currently participates in, these simple tips help ensure they’re safe, supported, and challenged in age-appropriate ways.

Support healthy play by

- Creating safe and open places to play.

- Making time for unstructured play

- Respecting all stages of play

- Following children’s lead when playing

- Joining in play when invited

- Gently encouraging children onto the next stage of play

1. Create Safe and Open Play Spaces

Kids need room to move! It’s better to have fewer toys and structures and more open space for them to use in any way they like. When you invite kids over for a playgroup or playdate, narrow down the toys they have to play with, or choose a space where they’re free to move around and play as the spirit takes them.

2. Make Time for Unstructured Play

As kids get older, you’re likely to start filling their schedule with lessons, sports, and other structured activities. Be sure you build in time for unstructured play, too! Tip: If your child finds themselves with an afternoon of free time and has no idea what to do with it, they’re probably not getting enough unstructured play time on a regular basis. Offer some suggestions, like “Let’s build a fort!” or “How about creating a village in the sandbox for your toy people?”

3. Respect All Stages of Play

As kids get older, you’re likely to start filling their schedule with lessons, sports, and other structured activities. Be sure you build in time for unstructured play, too! Tip: If your child finds themselves with an afternoon of free time and has no idea what to do with it, they’re probably not getting enough unstructured play time on a regular basis. Offer some suggestions, like “Let’s build a fort!” or “How about creating a village in the sandbox for your toy people?”

4. Don’t Over-Direct Play

Instead of, “Here, let me show you how to put those blocks together,” say, “What do you think we can build with these blocks?” Resist the urge to jump in and show them how to do everything “the right way,” and don’t get angry if they play games by different rules. Accept their lead and follow it, or simply step back and observe what they do.

5. Join In When Invited

Those moments when a child actively wants to spend time with you go by faster than you think. Join in enthusiastically, praise their creativity, and let them show you new ways to have fun!

6. Gently Encourage Children to Move to the Next Stage

The key here is gently—and only when it’s age- or developmentally-appropriate. The best way to do this is by modeling behavior. “Let’s ask those kids if we can play tag, too,” or “Can Maria share your crayons and draw her own picture?” Do not force your child to move on. If you’re worried that they aren’t progressing through the social stages of play as they should, talk to your child’s teacher or pediatrician.

Why These Stages Matter for Learning and Development

Child development experts now consider play so essential that Unicef’s Convention on the Rights of the Child includes it as article 31: “That every child has the right to rest and leisure, to engage in play and recreational activities appropriate to the age of the child and to participate freely in cultural life and the arts.”

An April 2012 report on The Importance of Play states: “The evolutionary and psychological evidence points to the crucial contribution of play in humans to our success as a highly adaptable species. Playfulness is strongly related to cognitive development and emotional well-being.” The report also noted that play has an important role in language development, self-regulation, and metacognition (learning how to learn).

Perhaps Fred Rogers, beloved television host of the show Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood, summed it up best: “Play is often talked about as if it were a relief from serious learning,” he wrote. “But for children, play is serious learning. At various times, play is a way to cope with life and to prepare for adulthood. Playing is a way to solve problems and to express feelings. In fact, play is the real work of childhood.” Decades of research all point to the same conclusion: all stages of play matter.

Stages of Play FAQ

What are the 6 stages of play development?

The 6 stages of play include unoccupied, solitary, onlooker, parallel, associative, and cooperative play and are based on the research of sociologist Mildred Parten. Parten developed her theory of the six stages of play based on her 1929 doctoral dissertation, which was published in 1932 and identified six stages of play based on her observations of preschool children aged 2 to 5. She grouped these into non-social and social categories, noting that children typically move through them as they develop, though not in a fixed order. The stages remain widely recognized today, with age ranges serving as flexible guidelines rather than rigid benchmarks.

What’s the difference between solitary play and parallel play?

In solitary play, children play independently and alone. They are completely focused on their own activity or game and may not even realize others are there. In parallel play, kids play side-by-side with each other. They still focus on their own play and don’t communicate much with those nearby. However, they are aware of other children and may occasionally watch and imitate what they do. Parallel play is important because it helps children develop social awareness and become comfortable in social environments.

When do kids start playing together?

Around the age of three, children begin associative play, sharing toys and play spaces but without any structure or shared goals. They begin learning how to share and compromise, making room for others to play while still staking out space for themselves. At the same time, they may engage in onlooker play, watching other children or groups closely to learn more about what they’re doing.

By age four or five, most children begin to join in cooperative play. They’ve developed enough social awareness and emotional intelligence to learn and follow the rules, take turns, and navigate conflict. Adults offer guidance, but children begin to play more and more independently as they get older.

Remember that ages are only guidelines when it comes to the stages of play. Kids move back and forth freely between stages. If you’re concerned that your child hasn’t begun playing cooperatively with other children by the time they reach school age, talk to your child’s pediatrician or teachers.

How can I encourage my child to move to the next stage of play?

Model the behaviors you’d like your child to try. You might say, “Your blocks look like a lot of fun! Do you mind if we sit down and play with them too?” This could encourage a child to begin exploring parallel or even associative play.

Don’t push your child to advance if they’re not ready. Some kids need to spend more time as onlookers before they’re confident enough to join in. If you feel like your child needs a nudge, though, it’s okay to ask, “Why don’t you ask if you can play catch too? Do you want me to come with you when you go talk to them? If not, I’ll be right here if you need me.”

How do I know if my child’s play is age-appropriate?

You can use the ages listed here as very general guidelines, but remember that children move back and forth through the six stages at their own pace. If you’re concerned your child isn’t showing any of the behaviors usually associated with their age, talk to a professional like your pediatrician. It could indicate a delay in social development, which can often be helped through therapy or other interventions.

Legal disclaimer: Any information, materials, or links to third-party resources are provided for informational purposes only. We are not affiliated with and do not sponsor/endorse these third parties and bear no responsibility for the accuracy of content on any external site. All information provided in this article is current as of May 2025.